You can now vote for Mollusc of the Year!

In 2021, the Great Paper Boat (Argonauta argo) was the winner – this year five other mollusc species are competing in a public vote for the title “Mollusc of the Year 2022”. They were selected from around 50 nominations from all over the world, by a jury of scientists. For the winning species, scientists will decode its entire genetic information.

Hardly any group of living organism is as diverse and species-rich as molluscs, which form the second largest animal phylum after arthropods. But as much as they differ in size, shape, behaviour and preferred habitats: What they have in common is that they have neither bones nor teeth and their bodies consist of a head, a “foot” – a strong muscle for locomotion – and a sac for the intestines. Most species live in the water.

Although molluscs evolved about 500 million years ago, they are still one of the largely unexplored groups of animals, especially from a genomic point of view. Many species are even still waiting to be discovered. There is also a lot of information missing that could help to understand their evolutionary development, relationships, adaptations and behavioural patterns. While the decoding of the genetic material of many other animal tribes is in full swing, there are only a few species among the molluscs whose genome has been completely sequenced.

This is where the international “Mollusc of the Year” competition comes in, which was launched at the end of 2020 by scientists from the Senckenberg Natural History Museum, the LOEWE Centre for Translational Biodiversity Genomics (TBG) and Unitas Malacologica, the worldwide society for mollusc research. “Our goal is to draw more attention to molluscs and make them better known,” explains Dr Carola Greve, laboratory manager at the LOEWE Centre TBG. “Last year we were very surprised and pleased to see how many interesting and rare species were nominated by researchers, but also from the public. Now we are excited about the new competition!”

Among the five nominated species are three species of snails, one species of mollusc and one barge-foot, commonly known as elephant’s tusk shell. The snails are represented by the delicate, transparent sea butterfly (Cymbulia peronii), a sediment snail with a conical, evenly structured shell (Telescopium telescopium) and a colourful, air-breathing land snail (Polymita picta) which was also nominated last year. Could 2022 be its break-through year? Marine bivalves include shell-less shipworms (Teredo navalis), which digest wood and play a key role in the global carbon cycle by processing plant biomass in the oceans. The barge-foot (Fustiaria rubescens) lives in the seabed and its long shell shape is reminiscent of a small elephant’s tusk.

The five nominees for the “Mollusc of the Year 2022”

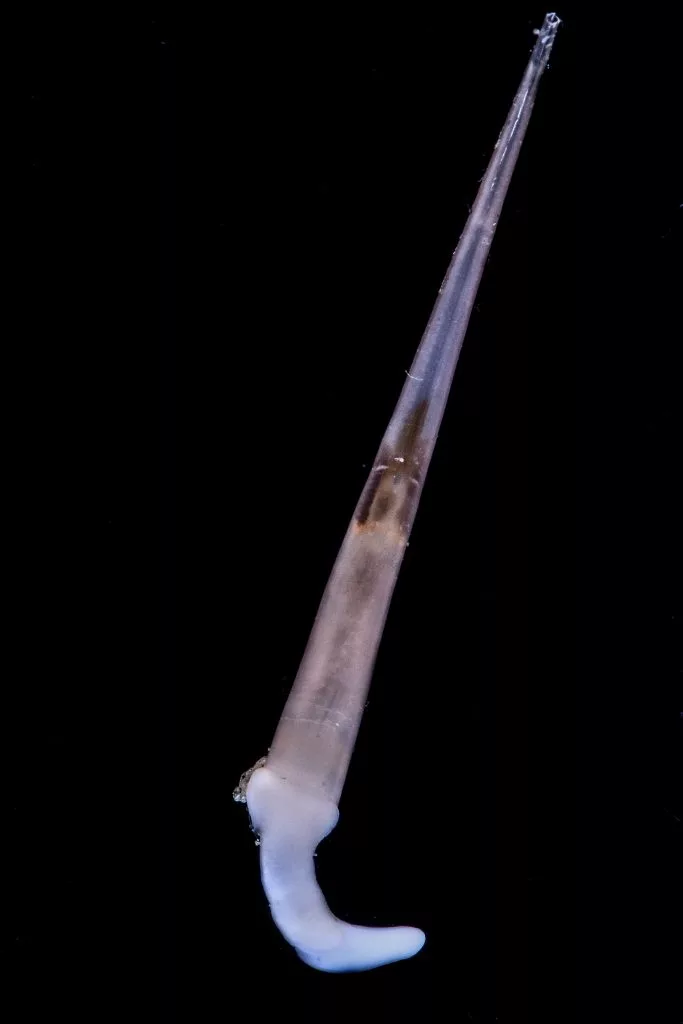

Fustiaria rubescens, the Barge-footer

What is it? Hi! I am Fustiaria rubescens, a scaphopod, you may know me as a tusk or tooth shell, although some people think that I look more like an ear swab. But do not panic, despite my tooth shape I won’t bite you because I feed on little microscopic organisms, especially foraminiferans. Only a few scientists have been able to study me, and so there are still great secrets to be discovered in the youngest class of molluscs (ca. 359-323 million years ago).

Where do they live? You may find me in both the Mediterranean Sea and in the Eastern Atlantic Ocean, inhabiting muddy bottoms, normally offshore. Yet, other scaphopods can be found all over marine environments.

What do they look like? My shell is an elongated tusk perforated on both sides. I live upside down buried in the bottom, and you can only see the thinnest tip, through which water enters and circulates along the mantle for the exchange of water and oxygen, as well as excreting waste. Completely blind and with my head buried, I search for food with special sensory tentacles known as captacula.

What secrets will this genome reveal? Knowing my genome could shed light on the processes of shell spiralization of me and my other molluscs mates, particularly my relatives the gastropod snails, as well as have a broader knowledge about my development (e.g., nervous system). I don’t know why, but my group is one of the most unknown molluscs and there is no single scaphopod complete genome sequenced to date. So, I think it is time to pay the attention we deserve and help me solve this puzzle. Would you take a step forward and vote for me?

Telescopium telescopium, the Telescope Snail

What is it? The Telescope snail, also known as the Horn snail, Berongan, Rodong and Mud creeper, is a rare type of gastropod mollusk that is associated with the Potamididae gastropod family.

Where do they live? Mangrove forests along the Indian Ocean are its native environment. Currently known dwellings include the mangrove regions of the following countries: Pakistan, Goa (India), Chantaburi Prov. (SE Thailand), Panglao (Philippines), Queensland (Australia), Northern Territory (Australia), Western Australia, Singapore, Madagascar, Réunion Island, Cambodia, Indonesia, Iran, Malaysia, Vietnam, and Papua New Guinea.

What do they look like? Telescopium telescopium shells are either black or very dark reddish brown. It can be easily recognizable by its long, cone-shaped shell with even like structure. They also have a fold on the columella of their shells, which makes them the only gastropod in the Potamidiae family to have so. Despite the obvious color of the shell they are often covered in barnacles and mud obscuring the natural color.

What secrets will this genome reveal? Telescopium is a mangrove inhabitant. Mangroves are found in two different areas (pristine and polluted) on Pakistan coastline. Many gastropod species of mangrove areas have been disappeared due to anthropogenic and industrial pollution, while T. telescopium is surviving under pollution stress. The genome will reveal the secret how the present species is surviving in polluted areas and what changes it has adopted from the environment while other species of gastropods have been diminished from the same areas. Also it will be comparative findings between polluted and non-polluted areas representing the important habitats of the mentioned species.

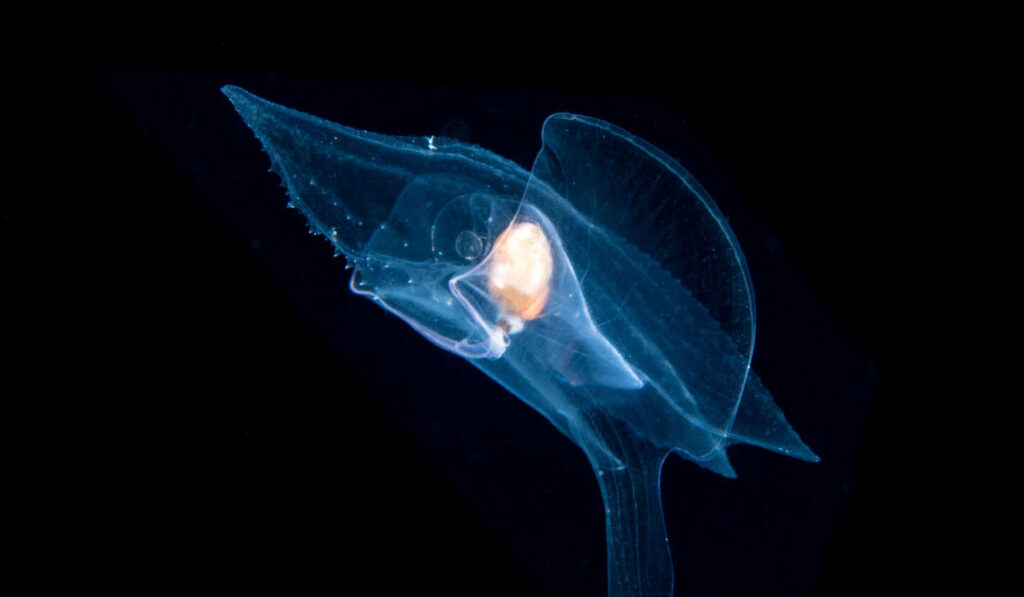

Cymbulia peronii, the Sea Butterfly

What is it? Cymbulia peronii is a large species of pteropod, snails that spend their entire lives drifting in the open sea. It is the species that inspired French fishermen to coin the term “papillon de mer” or “sea butterfly” in the eighteenth century.

Where do they live? The species has been reported from all oceans around the world. We don’t know how many there are, because they avoid plankton nets, and occur deeper than most other plankton (below 200 meters depth).

What do they look like? As a remarkable example of adaptation to pelagic life, these 6 cm wide mesmerizing animals have a gelatinous external shell in the form of a transparent slipper. They also have a snail foot that has transformed into two wing-like structures that enable them to “fly” through the water column.

What secrets will this genome reveal? Its genome will provide general insight into adaptation to life in the open ocean as well as shed light onto the molecular machinery needed to build their fragile shells. As our oceans are becoming more acidic, sea butterflies are widely used as “canaries in the coal mine” to indicate the impact of ocean acidification on marine calcifiers. Knowing their genome will be important for understanding their ability to adapt to the rapid ocean changes.

Polymita picta, the Painted Snail

What is it? An endangered Cuban snail famed for its colourful shell variation and enigmatic ‘love dart’, a device to stab mating partners to transfer ‘sexual hormones’.

Where do they live? Only in Eastern Cuba, in a wide variety of habitats, from xerophytic shrubs woodland to rainforests, and plantations where they benefit local agriculture by eating the moss and lichen on the leaves.

What do they look like? Possibly the most beautiful snail in the world, 2-3 cm across, in yellow, red, green, orange, white, black, or pink, with bold spiral bands. They are hermaphrodites, breeding in the rainy season with elaborate traumatic mating rituals, and living for around 1-2 years.

What secrets will this genome reveal? An assembled genome of this iconic species would provide the basis for understanding the evolutionary origin of the shell color variation and ‘love dart’ shooting behaviour. Moreover, as the snails are threatened with extinction – due to habitat loss and poaching – genomic resources would help establish units of conservation, ultimately protecting this species and as an umbrella to protect other species in the same habitatP

Teredo navalis – the Naval Shipworm

What is it? I’m a clam, but I look worm. In fact, people call me a shipworm. This is because, for thousands of years, I used to eat through the hulls of wooden ships. I even changed the course of history – just ask Columbus, I ate all his ships and stranded him in Jamaica! Sadly, maritime engineers have now come up with new paints and materials to stop me eating their boats.

Where do they live? I live worldwide throughout the tropics and subtropics. You can find me anywhere where there is plenty of wood in the water – from the pier at your favourite beach, to driftwood on the high seas, and the trees in mangroves swamps. Some of my shipworm cousins can even eat and burrow into rock!

What do they look like? As a juvenile, I take the form of a free-swimming larva, much like other bivalves. Once I have settled down on a tasty piece of wood and take my adult form, I look like a cross between a snake and a clam – long and bendy like a snake, but with a pale yellowy flesh like a clam.

What secrets will this genome reveal? There is outstanding potential (unfortunately for me!) for us shipworms to be a food of the future, reared on a mass scale for benefit to human health and the environment. We grow incredibly fast – some of us can reach over a metre in length in just 6 months. We can survive on waste wood and algae which can be grown using by-products from industry. We are incredibly nutrient rich, containing high levels of omega-3 and other important micronutrients. Our gills also contain many bacteria which could help develop new drugs, including antibiotics. In the past, we were considered villains. But our future (and our genome) may just help save humanity.