Stingrays can add up and subtract, as long as the numbers aren’t greater than five.

Suppose there are some coins on the table in front of you. If the number is small, you can tell right away exactly how many there are. You don’t even have to count them – a single glance is enough. Stingrays are astonishingly similar to us in this respect: they can detect small quantities precisely – and presumably without counting. For example, they can be trained to reliably distinguish quantities of three from quantities of four.

This fact has been known for some time. However, the research group led by Prof. Dr. Vera Schluessel from the Institute of Zoology at the University of Bonn has now shown that the species can even calculate. “We trained the animals to perform simple additions and subtractions,” Schluessel explains. “In doing so, they had to increase or decrease an initial value by one.”

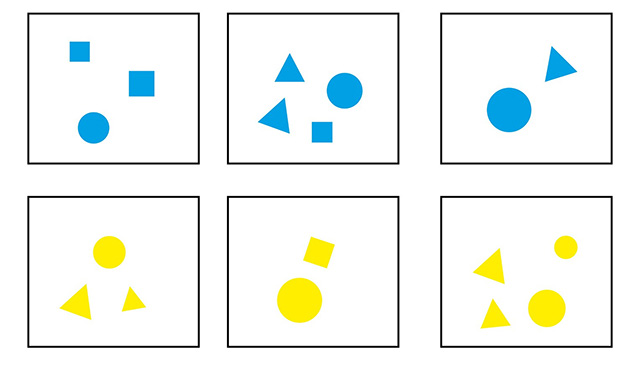

Blue means “add one,” yellow means “subtract one”

But how do you ask a fish for the result of “2+1” or “5-1”? The researchers used a method that other research groups had already successfully used to test the mathematical abilities of bees: They showed the fish a collection of geometric shapes – for example, four squares. If these objects were coloured blue, this meant “add one”. Yellow, on the other hand, meant “subtract one.” Just like in children, the rays learnt addition more easily than subtraction.

But can the fish apply this knowledge to new tasks? Had they actually internalized the mathematical rule behind the colours? “To check this, we deliberately omitted some calculations during training,” Schluessel explains. “Namely, 3+1 and 3-1. After the learning phase, the animals got to see these two tasks for the first time. But even in those tests, they significantly often chose the correct answer.” This was true even when they had to decide between choosing four or five objects after being shown a blue 3 – that is, two outcomes that were both greater than the initial value. In this case, the fish chose four over five, indicating they had not learned the rule ‘chose the largest (or smallest) amount presented’ but the rule ‘always add or subtract one’.

The fish have complex thinking skills

This achievement surprised the researchers themselves – especially since the tasks were even more difficult in reality than just described. The fish were not shown objects of the same shape (e.g. four squares), but a combination of different shapes. A “four”, for example, could be represented by a small and a larger circle, a square and a triangle, whereas in another calculation it could be represented by three triangles of different sizes and a square.

“So the animals had to recognize the number of objects depicted and at the same time infer the calculation rule from their colour,” Schluessel says. “They had to keep both in working memory when the original picture was exchanged for the two result pictures. And they had to decide on the correct result afterwards. Overall, it’s a feat that requires complex thinking skills.”

To some it may be surprising because fish don’t have a neocortex – the part of the brain also known as the “cerebral cortex” that’s responsible for complex cognitive tasks in mammals. Moreover, the rays don’t require particularly good numerical abilities in the wild. Other species might pay attention to, say, the amount of eggs in their clutches. “However, this is not known from stingrays,” emphasizes the zoology professor at the University of Bonn.

The rays are opportunistic feeders not hunters, they don’t nest and there is no information about preferences for particular sized social groups. Not all of the individuals involved in the tests managed to learn to calculate, but those that did were very good at it.

She also sees the result of the experiments as confirmation that humans tend to underestimate other species – especially those that do not belong to our immediate family or mammals in general. Moreover, fish are not particularly cute and do not have cuddly fur or plumage. “Accordingly, they are quite far down in our favour – and of little concern when dying in the brutal practices of the commercial fishing industry”, says Vera Schluessel.

The research confirms previous findings that fish possess many of the same cognitive abilities and to a similar extent as birds and mammals.

Further Reading

Publication: V. Schluessel, N. Kreuter, I. M. Gosemann & E. Schmidt: Cichlids and stingrays can add and subtract ‘one’ in the number space from one to five; Scientific Reports; https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-022-07552-2

Main photo credit: © Photo: Prof. Dr. Vera Schlüssel/University of Bonn