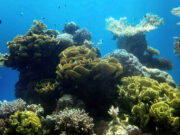

Researchers at Hawai’i Institute of Marine Biology (HIMB) have shown that, contrary to most projections, coral reefs are not inevitably doomed, but have the potential to persist and adapt over time, if carbon emissions are curbed and local stressors are addressed.

HIMB researchers created 40 experimental systems known as “mesocosms,” which mimic the diversity and

environment of a coral reef in the wild. The mesocosms included eight of the most common Hawaiian coral species, reef sand, rubble, and a menagerie of creatures which helped represent one of the most diverse ecosystems on the planet. For two years, the team exposed the mesocosms to different scenarios of higher temperature, higher acidity, or a combination of both ocean stressors to see how the reef communities would react to future climate scenarios.

“We included the eight most common coral species in Hawai‘i, which constitute about 95% of the coral cover on Hawaiian reefs, and many of the most common coral types across the Pacific and Indian Oceans,” explains HIMB post-doctoral researcher and lead author of the study, Christopher Jury.

“By understanding how these species respond to climate change, we should have a better understanding of how Hawaiian reefs and other Indo-Pacific reefs will change over time, and how to better allocate resources as well as plan for the future.”

Image: DepositPhotos

Image: DepositPhotos

Reef structures form over time through a process known as “calcification” where individual coral organisms—or polyps— build their own skeletons by becomes limestone. Coral reefs are naturally eroded by a variety of species, and if the balance between reef producers and reef eroders shifts, coral reefs could disappear, and the huge diversity of species which live on coral reefs would have nowhere to live.

As the ToBo lab research team controlled levels of temperature and acidity in the mesocosms, they measured the calcification responses of the eight species of coral, the reef communities, and the biodiversity of these systems.

“These experimental reef communities persisted as new reef communities rather than collapsing,” shares Jury. “This was a very surprising result, since almost all projections of reef futures suggest that the corals should have almost entirely died, the reef communities should have experienced net carbonate dissolution, and reef biodiversity should have collapsed. None of those things happened in this study.”

Their results are unique, and so is the ToBo lab’s approach to how they study their subject.

“Rather than focusing on just one or two species in isolation, we included the entire complement of reef species from microbes, to algae, invertebrates, and fish, under realistic conditions they would experience in nature,” notes Rob Toonen, co director of the UH Marine Biology Graduate Program, HIMB Professor and Ruth Gates Endowed Chair, and co-senior author of the study.

“These more realistic mesocosm experiments help us to understand how coral reefs will change over time.”

These findings suggest that coral conservation in a changing world is possible but urgent action is essential for these unique ecosystems to persist.

Further Reading

Christopher P. Jury et al, Experimental coral reef communities transform yet persist under mitigated future ocean warming and acidification. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 121 (45) e2407112121

Image credits:

- Hawaii reef fish: DepositPhotos