Table of Contents

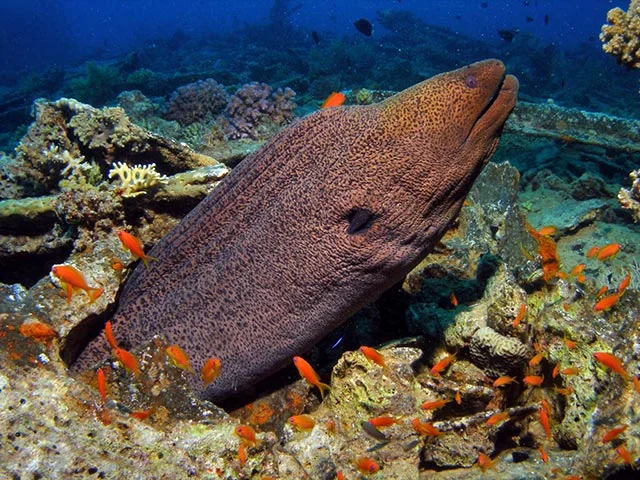

1. They are enormous

The biggest giant moray eel known was 3 m (10 feet) long and weighed 30 kg (66 lb).

2. They can be dangerous

Although large, they are not normally dangerous to divers. But they are powerful fish with sharp teeth that can inflict serious wounds if provoked.

John E Randall, writing in Australian Natural History Volume 16 Issue 06 recounts.

“The man was spearing a large moray eel for the Marine Toxins Program of the Hawaii Institute of Marine Biology. He followed a policy of spearing an eel and then returning to the boat for about 15 minutes. During this waiting period, the eel was expected to die or be sufficiently weakened to be easily pulled free of its hole and safely transported to the boat. One good-sized eel was apparently little affected, for it extricated itself from the spear and bit the man in the shoulder.”

3. They are poisonous

Don’t eat them as they cause ciguatera fish poisoning. Symptoms include nausea, vomiting, diarrhoea, headaches, muscle aches, numbness, vertigo, metallic taste in the mouth, blurred vision and hallucinations. Severe ciguatera toxicity can cause a feeling of a burning sensation on coming in contact with a cold object. Signs and symptoms can last from weeks to year and a relapse may be triggered by consuming alcohol, nuts, seeds, fish, chicken or eggs.

Ciguatoxin occurs in dinoflagellites, small organisms which stick to coral and algae. These are consumed by herbivorous fish. The fish in turn are eaten by larger fish and the toxin becomes more and more concentrated up the food chain until it reaches the giant moray eel. Once thought to be confined to the South Pacific and Caribbean, the toxin was recently isolated in the Red Sea and the Atlantic Ocean.

4. They hunt with groupers – helping each other

Giant morays co-operate with grouper in a hunt. A hungry grouper will seek out a giant moray and hover in front of it, shaking its head. The moray joins it and the hunt begins.

Normally grouper hunt during the day and giant morays during the night. Grouper hunt in midwater, so prey fish hide in crevices in the coral. Morays, though, squeeze through holes in the reef to corner their prey. Consequently fish swim into open water to avoid them. When the grouper and the moray work together though, they are very difficult to evade.

This behaviour lets the grouper catch five times as many fish as on its own. The moray caught even more fish than the grouper.

5. And co-operate with tiny wrasse

The eel is being cleaned by a Bluestripe Cleaner wrasse (Labroides dimidiatus). It is eating parasites and dead tissue off the eel’s skin. This keeps the eel’s skin healthy whilst providing a meal for the wrasse. It’s helpful cleaning duties give it protection from being eaten by the larger fish. An example of mutualism.

6. Giant moray eels change sex

Morays undergo a sex change during growth, changing from male to female.

References

Traylor J, Singhal M. Ciguatera Toxicity. [Updated 2023 Jun 26]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing; 2024 Jan.

Randall, J.E. 1969. How Dangerous is the Moray Eel? Australian Natural History. June 1969: 177-182.

Bshary R, et al. Interspecific communicative and coordinated hunting between groupers and giant moray eels in the Red Sea. PLoS Biol. 2006 Dec;4(12):e431.

Giant Moray Eel, Gymnothorax javanicus. SCUBA Travel. 2024